Hamid Ansari: Debate in House ensures different views… Why not let that happen?… Must allow process of scrutiny

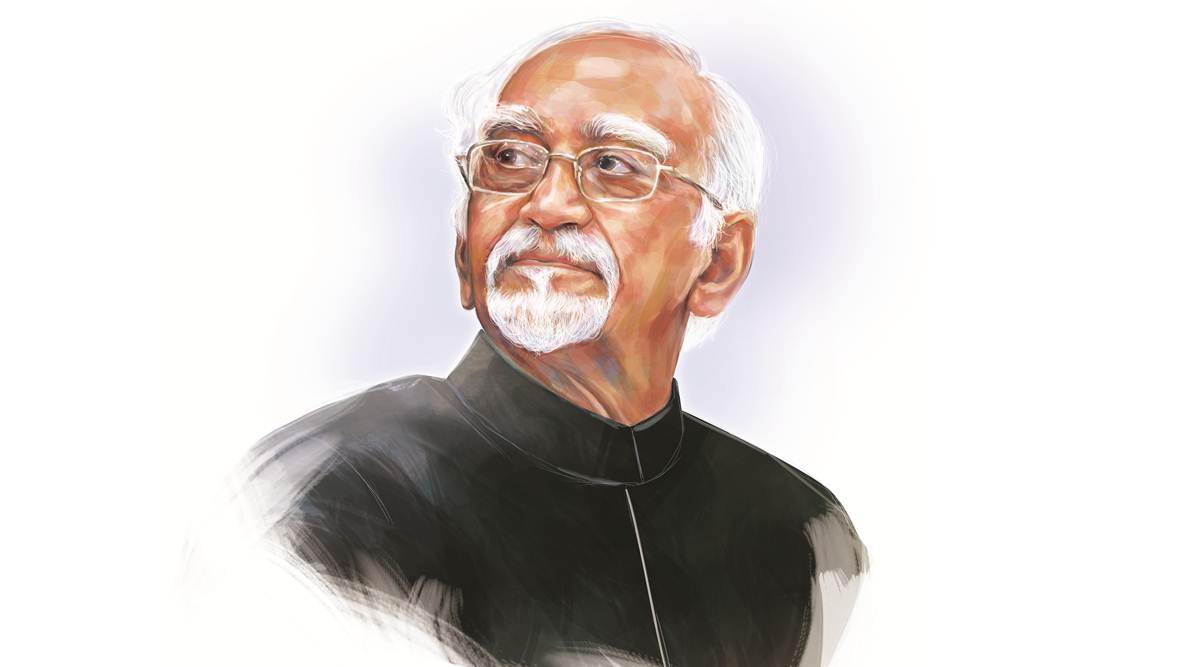

The former vice president reflects on his interactions with PM Modi, proposes de-escalation of conflict between India and Pakistan though “soft power”, believes India must move from tolerance to acceptance of minorities, and talks about his love for cricket. The session was moderated by Senior Associate Editor Amrith Lal

AMRITH LAL: At one point in the book you write, “The NDA, on the other hand, felt that its majority in the Lok Sabha gave it the ‘moral’ right to prevail over procedural impediments in the Rajya Sabha.” You then go on to recall how once the Prime Minister came to your Rajya Sabha office and said that there are expectations of higher responsibilities for you, “but you are not helping me. Why are Bills not being passed in the din?” How do you look back on your relationship with the PM?

My relationship with the Prime Minister was extremely cordial during the period of his chief ministership, prime ministership, and post my demitting office. Now about the “moral right” issue. Actually, the idea was floated by the late Mr Arun Jaitley when he was Leader of the House in Rajya Sabha. He drew upon a certain happening in the British parliament where if the governing party has a majority in the House of Commons, then the House of Lords has no role in debating or stalling it (the Bill). Now, it came out as a suggestion in the Rajya Sabha, and it was corrected that there is a difference between the House of Lords in London and the Rajya Sabha in India, because the House of Lords is a nominated House, whereas the Rajya Sabha is an elected House, although elected by a different process, but nevertheless, an elected House. And, if you see the text of the Constitution of India, wherever the two Houses of Parliament are mentioned, the Rajya Sabha is mentioned before the Lok Sabha, and the rights of the Lok Sabha and the Rajya Sabha are clearly spelt out.

There is one point on which Lok Sabha has an overriding precedence — in Article 109 with regard to money Bills. A Bill becomes a money Bill when the honourable Speaker certifies it. An effort was made during the NDA period that whatever was certified by the Speaker has to be accepted as a money Bill… many members in the Rajya Sabha felt that would not be correct. In fact, one member, if I recollect correctly, had gone to the Supreme Court on it… But there has been no decision… So apart from that, the Prime Minister had a point of view and in a certain meeting he expressed his point of view. I replied to it. That did not affect our relationship.

AMRITH LAL: In the book, in the context of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, you talk about hasty law-making and its impact on people. You say that this can be avoided by closer scrutiny and wider consultation. The suggestion can be applied to farm laws as well, which has led to protests for over two months now. What would your advice to the government be?

See, the view I took fairly consistently is that if you have a consensus, that’s one thing. But if there are points of view which differ, then the correct thing is to have a debate. And, at the end of the debate, if somebody demands a vote, then you go for the vote. This is a position which is well understood by everybody. Taking shortcuts does not help. After all, what is our parliamentary procedure for legislation? All proposals for legislation are drafted with great care by very knowledgeable brains on the Treasury benches and through a support system of experts. But you can have more than one view on the same thing. The benefit of taking these suggestions and to debate it in the Lok Sabha or the Rajya Sabha is that there is a compendium of different perceptions, views, expertise… So why not let that happen? Because, after all, as we have seen in our own country on innumerable occasions, a proposal becomes law after it is passed. But then some intelligent lawyer runs to the high court or the Supreme Court and the courts take a different view. So, to minimise that possibility, you should allow the process of scrutiny to take place.

The principal difficulty that is arising now, as I see it, is that Parliament is not spending sufficient time on its assigned duties. If you look at earlier records, Parliament was in session for 90-100 days, now it is sitting for about 60 days. The amount of work that can be done in 100 days is very different from what can be done in a truncated period of 60 days. That is where the difficulty lies. If we were to go back to the earlier practice, then there would be more space for discussion, debate, accountability… What is the structure of parliamentary government? Our structure is spelled out in the Constitution… The legislature has a function, the Executive has a function, the Judiciary has a function, but the functioning of the Executive is subject to scrutiny by the legislature. There are prescribed procedures by which that scrutiny takes place. So, allow those procedures to be operationalised. And once you allow that process to start, then many things get clarified. That was my view and I think I succeeded in implementing it.

As far as the role of the Chairman is concerned, from the first day to the last, I had one consistent view that the Chairman is a referee in a hockey match. He’s not a player, but he watches the play very closely. And, as long as the play is according to rules, his function is simple, to watch. But if rules get violated, then the rule book in his pocket has to be invoked.

AMRITH LAL: The stalemate and protests over farm Bills drew social media responses from international celebrities recently. The Ministry of External Affairs then issued a press note stating that it is “unfortunate to see vested interest groups trying to enforce their agenda on these protests, and derail them”. As a former diplomat, do you think this is the right way of handling criticism from international voices?

The instrument in the hands of the diplomat is talking and persuasion. He has no guns, no dandas. Persuasion is necessary and trying to locate a common point is important. Sometimes you have to concede a bit here to gain something more elsewhere. I wouldn’t like to comment on what the recent response (of the MEA) was… I think there have not been too many occasions when resorting to (such statements) has taken place. Let us see how it plays out, because I think it’s very much now in the public domain.

AMRITH LAL: You use a lot of cricket references. In the book you talk about how a telegram by you from Kabul, with a lot of cricketing terminology, landed up on the prime minister’s desk. Can you tell us about the incident?

As a student, and even later, I was very involved in cricket. I used to be an umpire in my university days. And so the vocabulary of cricket has stuck with me. The incident you refer to is when I was posted to Kabul. It was the last days of the Najibullah regime, and things there were unpleasant. My United Nations colleague suggested to me that I get a special kind of film put on my windows as it would prevent the glass from shattering. I passed that back to Delhi and Delhi said yes, but added that we have to go through a certain process. That was taking some time and so one day I sent a telegram to Delhi. These were confidential communications addressed to a certain person in charge of these matters in the MEA. I knew that he was familiar with cricket terminology. I said, “If I have to field at the forward short leg, I need protective gear.”

Now, it so happened that the telegram arrived in Delhi on a Sunday morning and the usual scrutiny that is done in the Prime Minister’s Office of what telegrams should be shown to the prime minister in terms of importance and what should be attended to by agencies concerned of the government, could not be done. The whole bunch landed up on the table of then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi. He put a big red pencil question mark on it and sent it to the foreign secretary, who was also not aware of it. So there was an urgent query as to what on earth was I talking about, and in what language? That’s all it was, a bit of fun, but not necessarily at that point in time.

NIRUPAMA SUBRAMANIAN: We seem to have very difficult relations with all our neighbours now. Has it ever been this bad or is this a time of special churn in our relations?

Let me just say that relations with neighbours are always critical. You can choose friends who are distantly located, where your interactions are frequent and less substantive. Then there are friends who are located next door and you have an interaction every day on a whole range of subjects, whether it is hard politics, military questions, or whether they are questions which relate to water disputes or environmental disputes and similar things. So every government’s policy about the neighbourhood has to be… There are only two options, either a policy of seeking clear areas of cooperation, or a policy of conflict, trying to ride roughshod over them. I don’t think at this time, riding roughshod over neighbours, big or small, is a wise policy, and I don’t think it has been the policy of the government anywhere. So you have to seek areas of convergence of viewpoints. Take the case of water. We had a water dispute with two of our neighbours, at least. One dispute got settled a long time back through the good offices of the World Bank with the Indus Water Treaty, which has stood the test of different armed conflicts. So the wisdom of that remains in place. Then we have a dispute over water with Bangladesh. It has been resolved to a great extent but not completely. We have disputes with Nepal, again settled sometimes, not settled sometimes. You can multiply these examples in all fields. So, neighbourhood policy has always been a critical area of engagement.

NIRUPAMA SUBRAMANIAN: There hasn’t been any progress in our relationship with Pakistan for many years. What is the way forward?

Public opinion has to be cultivated, it has to be informed, and it has to be corrected at times… In this particular instance, both are nuclear powers. Is it possible to visualise conflict?… Wisdom always lies in seeking de-escalation. Now, where can de-escalation take place? The repertoire at our disposal is extensive. We have political relations, commercial relations, cultural relations — the soft power is very substantial. The Indian film industry is extremely popular across the border. Can we use it to our benefit instead of everything being smuggled through some country in the Persian Gulf. So, public opinion is not a monolith. There are people who are strategic thinkers, there are people who are ‘do or die’ in this lot.

I used to be, as vice-president, chancellor of Panjab University, Chandigarh. The university has a counterpart on the other side, the old Punjab University, Lahore. And the two universities communicated at the faculty level. So, there are possibilities and options… The whole challenge in diplomacy, as a famous Cardinal in France used to say, is to keep talking. Because only by talking will you be able to discover the areas where the dialogue can be furthered. But if you refuse to talk, then there is no possibility of locating these hot spots for a conversation. Where diplomacy is abandoned, then unfortunately, you have no option but to resort to other means of interaction which are not healthy….

AMRITH LAL: You have said that pluralism and secularism are extremely essential for a democracy like India. And then in the context of India’s large minority population, you say that there is a need for acceptance. Now, in domestic politics, where any kind of discussion about the rights of minorities is seen as appeasement, what is the way forward?

What is the existential ground reality? Ours is a very diverse society — not one identity but multiple identities. Each one of us has multiple identities. So, to expect or suggest that all these can be rolled into one through a steamroller is a non-functional suggestion. Secondly, we have the Constitution of India, drafted with great care by wise minds. What are its basic principles? Political justice, economic justice… But justice is operative. Another word which is operative is fraternity. If you put the two together, all citizens of the country have a fraternity. And (there is) dispensation of justice to everybody. There was a philosopher who said justice is the first principle of any society and it’s a fact of life… So, when I say pluralism is a fact of life, if you ignore it, you are ignoring reality.

We have to accept diversity and try to actualise it. This is where the challenge lies. If you have a mindset which denies diversity, then you run into trouble. But if you don’t have that kind of mindset, then you will be accommodative. That is why tolerance is not enough. Tolerance is a great virtue and societies that practice tolerance have to be commended. But we have to go beyond tolerance and say acceptance.

MANOJ C G: Going back to your interactions with the Prime Minister, in the book, you say that the Prime Minister asked you why are Bills not being passed in the din. After that conversation, did you allow any Bills to be passed in the din? And why didn’t you take a public stand then or talk about it in your farewell address?

The farewell address was not an occasion to talk about it… Prior to that conversation with the PM, we had come to a decision. I had said that there were various points about the functioning of Rajya Sabha which needed correctives. One of them was the onslaught on the Question Hour. Now, the rules of the House have been that the first hour shall be the Question Hour. But very often Question Hour was disrupted…which meant that a critical element of accountability of the Executive was superseded. So, after much thought and quiet talks with the members of the House and leaders of parties, I suggested that we move the Question Hour. We moved it from 11 am to 12 pm. These are procedural reforms which are reached when you feel the need for it. If everybody agrees, then good. The Chair cannot ride roughshod over the rules of the House. The rules have to be discussed and if there is broad agreement, amended. And that’s exactly what was done with Question Hour.

ZEESHAN SHAIKH: In a 2015 speech you had said that one of the major problems confronting Indian Muslims was their absence from decision making. Since then, things seem to have got worse. How can we rectify this problem?

As I said in that speech, there were two sets of grievances which were articulated from time to time. One grievance was related to the functioning of the Indian State, and the other was with regard to their own perceived problems. Now, for the latter, I said, these are matters that have to be corrected by the community itself… (through) education, empowerment… But then there are grievances in relation to the Indian State and the political system. The primary one is the need for security. There have been lapses in security from time to time. Why can’t more be done about it? And if lapses have taken place, what have been the correctives? As chairman of the minorities commission, I knew a great deal about it. Then there are grievances about the share in the largesse of the State. Do I get a fair share proportionate to my numbers and my needs from government programmes? That has been quantified at great length by professional economists in government reports but not implemented. That is also a subject in the reports.

The third thing is share in decision making. As a citizen, I have a right. I’m an equal stakeholder… Firstly, how many people speak up on these matters in Parliament or state Assemblies? The totality of wisdom does not lie with the government of the day, somebody has to flag these points. So that is all that I said. I had even said this in another speech, when PM Modi first used Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas. I welcomed it publicly but it requires that everybody in the race is at the same starting point. If somebody is lagging behind, then he or she will never be able to catch up. So, the point is equality of treatment, fraternity and all this emanates from dispensation of justice.

AMRITH LAL: Amrith Lal: In the same talk, you also spoke about “the failure of the (Muslim) community to engage with the wider community in sufficient measure”. Please elaborate.

I live within my own circle and I will not go beyond it; (I will) not talk to my neighbour if he doesn’t belong to my faith; not talk to others with whom I work. Obviously, something then goes missing. The (Muslim) community has to understand that it is part of a larger, very diverse, community. The kind of language that my neighbour speaks may not be my language, their festivals may not be my the festivals, but what is lost if I join as a Muslim?… Nothing is lost. It’s just a mindset to keep away. I should invite them to my festival and join them in their festivals. This is how India lives in villages.